Jane Austen’s Fan and a Ghostly Visitation

This autumn, I was invited by the Japan Foundation, London, on a UK book tour comprising six cities.

I had only just arrived when I caused a major incident. On my first stop in Cheltenham I flooded the bathtub, drenching the carpet in my hotel room.

In my defense, it was all because my time at the Cheltenham Literary Festival that day had been so eventful. So much had happened in those whirlwind hours that I was completely zoned out as I lay in the bathtub that night, recalling it all.

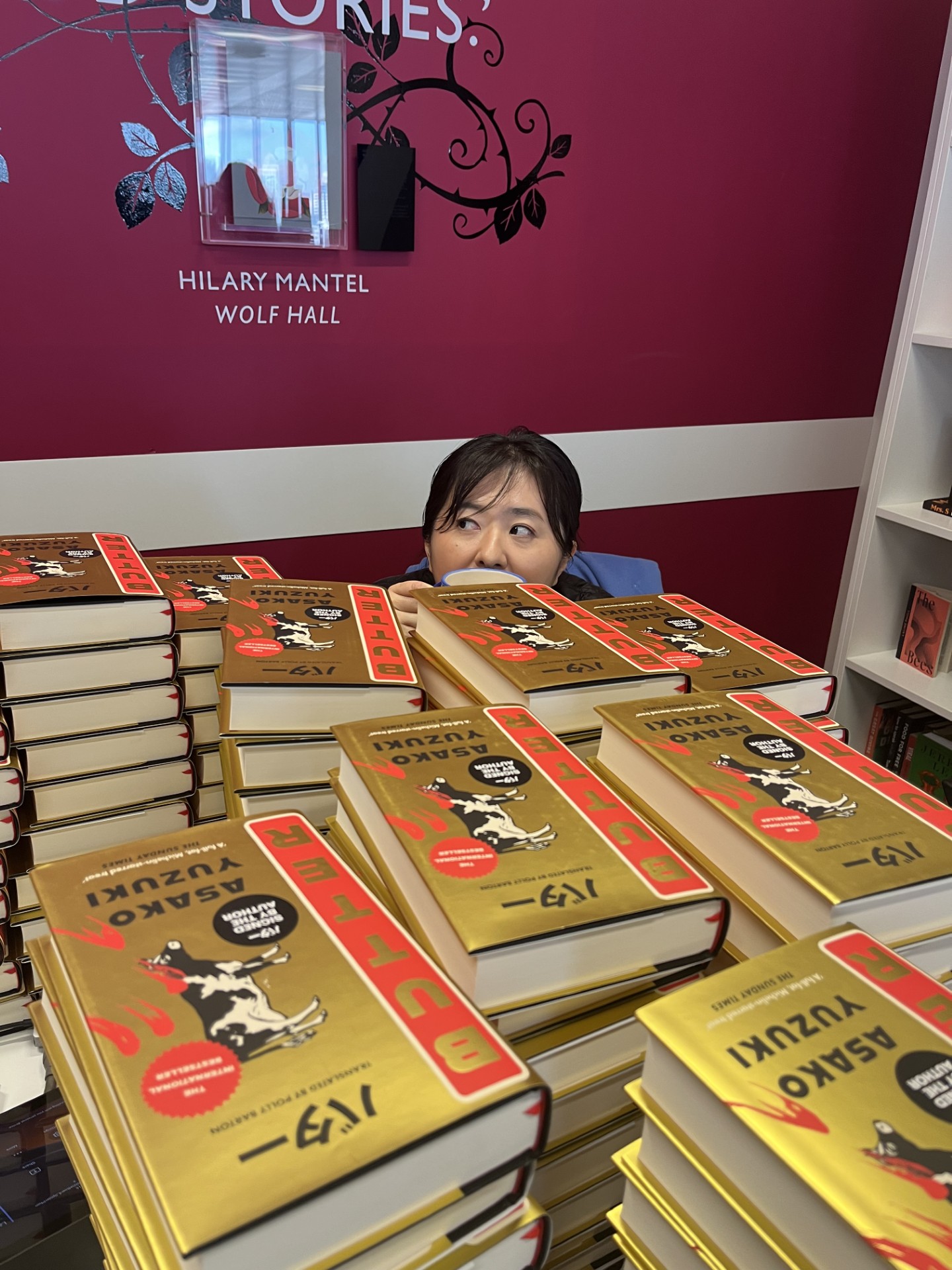

That morning, I’d headed from my hotel straight to the festival. I was shown to the authors’ tent, where speakers are allowed to relax between events. It had a buffet offering unlimited helpings of salad, meat, bread, and vegan options—wine and coffee, too. The bright-pink wristband that had been slipped onto my hand as proof that I was an author gave me free access to this place at any time. I left my bag and went out to explore the many tents spread across the green, only to run into a costumed figure surrounded by children. I felt as though I knew that bald head, those small eyes, and the shape of that nose…. Ah, yes! This was Greg from Diary of a Wimpy Kid by Jeff Kinney, a character I’d been so fond of as a child. Feeling somewhat surprised that this simple, doodle-like illustrated figure was sufficiently popular to appear here in mascot form, I had my photo taken with him. Over in the bookshop tent, I found piles of the new Sally Rooney book stacked in prominent position. I’d read two books by Rooney in Japanese translation, but here was a title I’d never heard of, a cover I’ve never seen. This was the moment it first hit me, properly, that I was in a different country. Nearby, the face of actor Stanley Tucci, of The Devil Wears Prada fame, beamed out from the covers of his autobiography. It seemed likely that this would take a while to make its way to Japan, if indeed it ever does, so I resolved to buy it despite my worries about adding to my luggage—until I checked the price and saw that it was the equivalent of 4,000 Japanese yen. I slipped it quietly back onto the shelf. The same thing had happened when I first saw the English edition of my own book, Butter, piled high in a bookshop—both the size of books overseas and the fact that their price is double what they would be in Japan always makes my heart race. To my eyes, the UK publishing industry seemed to be flourishing, the long line to the cash registers proof that the sale of paper books is thriving.

In a tent set up for panel discussions, I watched Takekawa Junko from the London office of the Japan Foundation speak about Sakuraba Kazuki’s Red Girls: The Legend of the Akakuchibas and Enchi Fumiko’s The Waiting Years, in the context of resisting the patriarchy. Just the idea of these Japanese female authors so beloved to me being discussed overseas got me terribly excited. Listening to Junko, I discovered that the Japanese author Ariyoshi Sawako had gone to the USA on a Rockefeller Foundation grant. I remembered that Ariyoshi’s work had grown more and more vital as time went on, taking on an ever broader perspective—perhaps a result of her seeing how things were in the West.

Making my way farther through the festival, I discovered a set of staged photo booths inviting children to dress up as characters from literary classics. The Sherlock Holmes one, for example, recreated a small room at Baker Street with a chair, pipe, and that distinctive hat on hand. I watched children transform themselves into the man, their parents snapping photos. I was transfixed by the nearby Jane Austen booth, where floral-print wallpaper and fancy furniture set the scene with a frilly bonnet, a folding fan, and other accessories to try on. The idea that the world of Austen was something that even children shared prompted a burst of envy at the height of the culture in this country. Unfortunately the bonnet wouldn’t fit my head, so I made do with the fan and a bandeau, asking a woman who had her kids in tow to take my photo. “Do you like Austen?” she asked. I replied with an unequivocal “Yes!”

In various bookshops throughout my UK tour, I encountered all kinds of Jane Austen merchandise: card games, mugs, and stationery emblazoned with pictures and quotes. Austen wasn’t the only one, either: the Brontë sisters, Agatha Christie, and Virginia Woolf were all featured on various kinds of goods. The Virginia Woolf jigsaw puzzle I found myself unable to resist, and ended up buying. What most impressed me were the illustrations—not cutesy cartoon versions, these, but rather period-style drawings. In Japan too, classical authors are featured on products and marketing material, and on souvenirs and merchandise based upon their works, but they’re usually represented in the style of contemporary anime characters. Here, it seemed as though the world of letters merged with people’s everyday lives quite naturally, without contrivance—that very little stands in the way of anybody accessing literature. I couldn’t put it into words that well at the time, but I was hit by the keen sense that this, here, was what I should be working toward.

At that evening’s event, an audience larger than any I’ve ever had in Japan filed their way into the tent. They laughed out loud at what I was saying, asked lots of questions, and formed a huge queue for the signing desk. If anything, I felt terrified by this turnout. Sure, I knew that Japanese literature was having a moment in the UK, but I felt that there must be some kind of mistake for my book to be doing this well. I don’t say this out of modesty, either: from my perspective, the UK is a progressive country, and I’d thought, quite simply, that the kinds of worries my characters have would not strike a chord with readers here. As the tour carried on through other cities, it began to dawn on me that this assumption was wrong, but that first evening I felt quite unable to process what had happened. Even after getting back to my hotel room, my ears were ringing.

Author event at the Cheltenham Literary Festival

Which was how it came to be that, while I lay there in a daze, the bathwater flowed over the sides of tub and flooded the room. In a panic, I gathered up all the towels I could find to mop it up, and even tried using the hairdryer, but the dark landmass that had emerged on the carpet didn’t grow any smaller. It was a classical boutique sort of hotel so I didn’t call for help, imagining that there would be nobody at the front desk this late at night. Resolving that I’d apologize first thing the next morning, I cranked up the heating and left it on overnight in a bid to dry out the carpet as much as possible, then sank into bed and closed my eyes.

Yet my head was crowded with unsavory possibilities. The building was old. Even as lay there, the water might be soaking into the wood, which would begin to decay, so that the whole property would slowly swell up and then crumble. I’d be hit with an extortionate fine. It would be too much for me to pay, and this would eventually lead to the downfall of the Japan Foundation. I thought of Ariyoshi Sawako. The idea of funding authors usually cooped up at home so they can cross oceans and meet with readers in other countries was the most extravagant, most meaningful use of money that I knew of, and so I’d spent the entire day in a trance of wonderment, but now this flood I’d caused would bring it all to an end….

I tossed and turned the entire night, haunted by visions. It wasn’t just Ariyoshi—the ghosts of numerous Japanese writers throughout history who’d received public funding to travel overseas came out to torment me in my dreams. The faces of various contemporary authors I knew also appeared, shouting angrily at me, laying bare their contempt. A hundred years in the future, at a lecture in the history of literature at some university somewhere, the professor mentioned my name as the person who had occasioned the demise of the Japan Foundation, and the students listening shook their fists in rage.

In the morning Junko, who’d come to meet me at reception, apologized along with me to the staff. “Oh, don’t worry about that!,” they responded cheerily, but still my dread remained. When they told me to come back next time, I replied that I hoped the carpet would be dry by then. It was only when they burst out laughing that I felt my remorse lift, and my nerves finally begin to settle.

In the days that followed, Junko and I visited universities, bookshops, and publishing companies across numerous cities. I had the opportunity to speak with many readers. The sense I’d had at the Cheltenham Literature Festival of the vigor of the UK publishing industry persisted. It seemed to me that everyone I met had the money to buy books and the time to read, and that the prevalence of literary agents creates a buffer between authors and editors, resulting in less room for toxic relationships and generally more breathing space. The booksellers didn’t seem to be unreasonably overworked. I picked up on a general sense of stability: it wasn’t just that books were selling, but that the whole country protected the institution of literature.

The continued positive reactions from my readers, which I’d mistrusted on my first day, led me to understand that Butter’s success here wasn’t just part of some boom. It turns out that a lot of UK readers, just as at home in Japan, are troubled by gender inequality and lookism, and had identified with the book. When I stepped away from the thriving elite world of the publishing industry and into local neighborhoods, I soon encountered things that gave me a sense of the disparity that exists in this society. I was still swooning over the heights of the culture here, while understanding at the same time that such culture lay on the flip side of the country’s exploitative past, and I also came to discover for the first time the UK’s links with the suffering in Palestine. When giving a talk at Oxford University, I recalled something I’d read in Virginia Woolf and commented that I’d heard that women weren’t allowed at Oxbridge in the past. In response, the female academics all asserted that similar discrimination exists today—that this is still a society in which men dominate, and it has to change. Of anything from this trip, it was this episode that left the strongest impression on me.

I had never before thought of myself as particularly well read, so it surprised me to realize through this tour that various works of British literature are as much a part of me as my own flesh and blood. I’d like to express my gratitude here to all the English-Japanese translators, and to the voice actors who dub films, for making the nuances of British English accessible to me over the years. The most startling revelation I had was how talking with people about books can make what formerly seemed like a huge distance evaporate like magic. This sudden contracting of distance brought into relief the inherent problems of a place that had previously seemed so dazzling and perfect.

The ghosts of Ariyoshi Sawako and others who’d visited me on that first night had said the same thing: for a writer, being funded to travel overseas can make a huge difference. It’s perhaps no exaggeration to say that every sight taken in can potentially shape the course of one’s future authorial life. Which is why I want to try to read all the books that people spoke to me of, or at least those that have been translated into Japanese. I’d love to return to the UK and tell those people that I’ve read them.

Next time, I’ll do my best not to fall asleep in the bathtub.

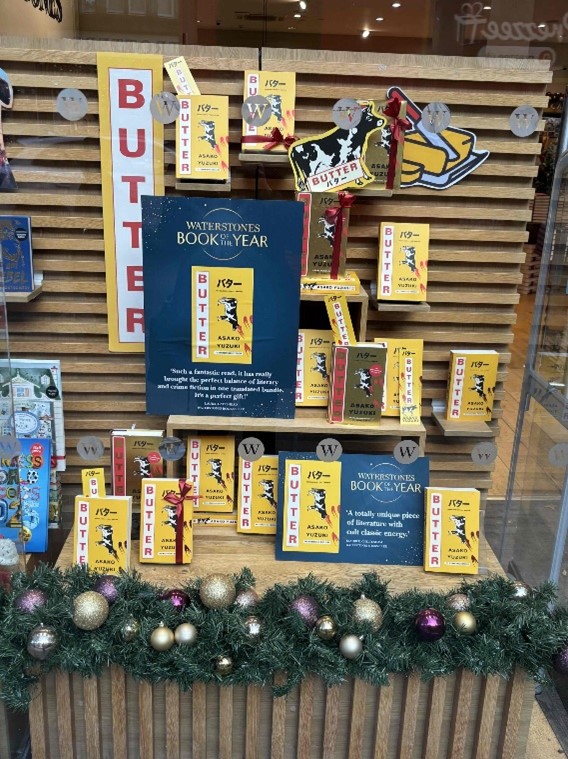

A window display of Butter,

Waterstones Book of the Year 2024